By Justin T. Carreno – February 23, 2021

To understand the story of African-Americans and firefighting in Arlington, it’s important to first know the history of African-Americans in the County during the Reconstruction and Industrial eras. It begins as far as back as May 1862. This was eight months before President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, when slaves in the District of Columbia were freed by an act of Congress. Fugitive slaves fleeing from the South soon flooded into Washington, DC, many of them moving into camps set up by the federal government. When smallpox swept through the overcrowded sites, however, Lt. Col. Elias M. Greene proposed that some of the freedmen could farm nearby land, and recommended the “pure country air” south of the Potomac in Arlington County (then Alexandria County). With this recommendation, the government established Freedman’s Village (some say by an act of payback) on a tract of land seized by the Union on the estate of General Robert E. Lee’s Arlington House, where today Arlington National Cemetery is located.

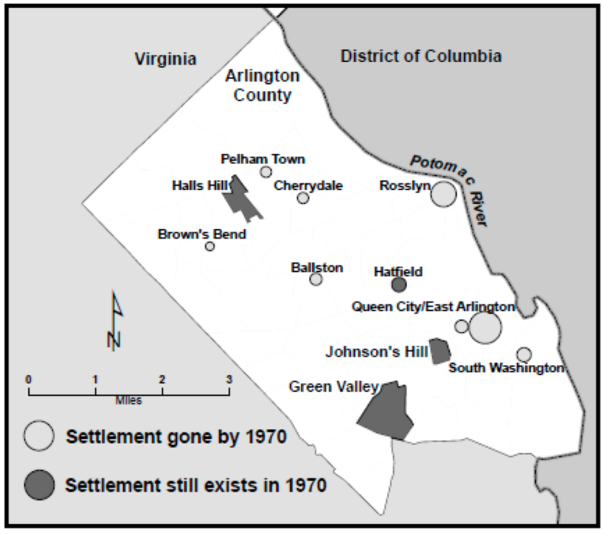

The government promotion of Freedman’s Village caught the eye of real estate developers, and through the 1890s began touting land in what is now Arlington County, luring Washington residents with promises of “quiet and repose from the stir and bustle and noise” of the city. Amid mounting public pressure, in 1900, Congress offered the people of Freedman’s Village $75,000 (approximately $2.5 million in 2021). This financial settlement was divided among the residents, and the village was torn down. In the early 1900s, Arlington was approximately 38% black versus present day, where it’s about 8.5% black. When the government disbanded the village, many of these 38% inhabitants went on to form Arlington’s four historically African-American neighborhoods, including Green Valley (also known as Nauck), Johnson’s Hill (now Arlington View) and Butler Holmes (now Penrose) in the areas around Columbia Pike, and High View Park-Hall’s Hill.

Throughout the early 20th century, most of the County’s black residents continued to live south of what is now Arlington Boulevard, where most residents worked in the service industry. The north, meanwhile, was dominated by professionals and old money. North Arlington was almost exclusively white, with the exception of one black neighborhood – the aforementioned High View Park-Hall’s Hill (or just Hall’s Hill), which now straddles Lee Highway a few blocks west of the intersection with Glebe Road – many of whose residents worked as servants in white homes, or as farmhands on nearby estates.

Hall’s Hill dates back to 1881, when local plantation and slave owner, Basil Hall, faced with plummeting property values in the aftermath of the Civil War, began selling off portions of his land to African-American neighbors, many of them former enslaved people. (Little did he know 15-20 years later, his property would be more valuable as Washingtonians began to migrate to Arlington).

At this same time, during the turn of the century and the early 1900s, as Arlington was getting increasingly settled, the need for emergency services was becoming more and more necessary, and in 1898 the first fire department in the County was established – Cherrydale Volunteer Fire Department (CVFD). Following CVFD’s lead, other fire companies were organized in the early 20th century around Arlington to serve County residents, but this didn’t include those living in black neighborhoods.

Now during the turn of the 20th century, segregation was in full effect. As a culturally Southern state, Virginia embraced Jim Crow. With the passage of the 1902 Virginia constitution, de facto segregation became the standard in all of Virginia. This being the case, the African-American enclaves became insular and self-sufficient because amenities and services were not afforded to these neighborhoods. This included emergency services. Fire departments, including Cherrydale, not providing services to black neighborhoods is what prompted Hall’s Hill to create its own fire department.

In 1918, the same year CVFD built their Central Fire House, Hall’s Hill Volunteer Fire Department (HHVFD), Company 8, was organized, made up of all black volunteers. It was the first all-black volunteer fire department below the Mason-Dixon line. Ironically, CVFD at this time had apparatus that with capability to respond to the Hall’s Hill area, but the lack of response during segregation drove Hall’s Hill to develop their own capability.

Seven years later in 1925 the only other African-American volunteer fire company in the County was formed in East Arlington (also known as Queen City) – the East Arlington Volunteer Fire Department. This department located in the aptly nicknamed, Hell’s Bottom, area was later disbanded by the County Board in February 1941 to prepare for the construction of the Pentagon. HHVFD continued to operate and in 1926 it became fully incorporated. In December 1935 the white-only volunteer companies formed an umbrella group, the Arlington Firemen’s Association, excluding the African-American VFDs from valuable protections afforded to the other fire stations (FS). In 1940 Arlington County became one unified fire department with all independent stations, including Hall’s Hill to officially be Arlington County Fire Department (ACFD). And In 1941 the County Board agreed to pay six of Arlington’s seven volunteer fire departments a monthly rate of $455 (approximately $8,400 in 2021) for designated professional firefighters. The Hall’s Hill VFD was excluded.

Finally, between 1951 and 1954, the County decided to pay eight paid firefighters at Hall’s Hill VFD, all African-American. But segregation and racism were still very much pervasive, and HHVFD would often not be called to big fires. During a huge inferno in Rosslyn almost all County fire crews were called in except those of HHVFD Station 8.

In 1967 Alfred Clark became the first African American fire captain in the County, serving at HHVFD Station 8. In an interview with his daughter, Kitty, she recounts white firefighters pushing back, and said they “refused to serve under a n*****.” When the battalion chief discovered this hostility, he directed the white firefighters to serve and respect Captain Clark.

By early 1963, all Arlington stations became fully integrated, with black and white members operating side-by-side. Of course, this didn’t mean there still wasn’t institutional racism within ACFD or individual racism among members.

In 1968, while other Arlington fire stations were dispatched into the District when riots broke out following the April 4 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, although there is no known reason, Hall’s Hill Station 8 was asked not to participate. Catie Drew, a current CVFD member, reported that one of the long-time black firefighters – Quentin Tapscott (now deceased) – would tell stories about working at Station 8, Hall’s Hill, through the 1960s and 1970s, and how white residents reporting emergencies in Station 8’s first due area (the area in which a fire company is expected to be the first to arrive on a fire scene) would tell the dispatchers not to send the black fire department, but only the white fire department.

Since then, ACFD has evolved culturally, and has become known as a diverse and, as stated in its vision statement, a progressive department. In fact, Arlington garnered national attention in 1974 when it hired the first female firefighter in the country, Judy Brewer, née Livers, serving for over 25 years, and who became a trailblazer and inspiration, not only for other women, but also for underrepresented groups, including African-Americans in fire departments across the country.

CVFD, since its founding in 1898, has also advanced and become a proudly ethnically and racially diverse organization. Among CVFD’s present-day diverse membership are the first black volunteer Firefighter/EMT and first black volunteer Fire Department Chief. Catie Drew who joined the department as its first African-American member in 1987, was trained as a fully operational firefighter and EMT, riding on both the engine and ambulance. Christopher Jones was elected as Cherrydale’s first African-American Department Chief in December 2014. Jones has not only been a dedicated leader, firefighter, EMT, but also a champion of progress at CVFD.

Having come a long way since it’s early days, Cherrydale Volunteer Fire Department, alongside it’s paid counterpart, Arlington County Fire Department, is not only dedicated to the mission of preserving life and property, but also has a strong commitment to professionalism, diversity, equity, inclusion, and adapting to meet the needs of the entirety of the Arlington community.

Justin T. Carreno is a volunteer firefighter/EMT and serves as the Historian for the Cherrydale Volunteer Fire Department in Arlington, Virginia.

Sources:

- https://library.arlingtonva.us/2015/08/04/legacy-halls-hill-vfd-and-station-no-8/ (Arlington Public Library)

- http://arlingtonfirejournal.blogspot.com/2005/03/today-and-yesterday.html (Arlington Fire Journal)

- https://www.arlingtonmagazine.com/are-there-two-arlingtons/ (Arlington Magazine, “Are There Two Arlingtons?”)

- https://www.arlingtonmagazine.com/land-of-the-free/ (Arlington Magazine, “Land of the Free”)

- https://themetropole.blog/2019/02/21/african-american-life-in-arlington-virginia-during-segregation-a-geographers-point-of-view/ (The Metropole, “African-American Life in Arlington, Virginia, During Segregation: A Geographer’s Point of View”)

- http://www.civfed.org/2011fire.pdf (Arlington County Fire Department, Overview)

- Cathleen Drew, Cherrydale Volunteer Fire Department member, interview/email correspondence